The Third Police Precinct burns in Minneapolis, 2020 (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Before the Flames Take Hold: On Jasper Bernes’ The Future of Revolution (2025)

Trey Taylor

12 September 2025

12 September 2025

‘Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself’, Marx wrote in The German Ideology (1846). Instead, ‘we call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things.’ Such a declaration indicates two intertwining positions - one political, the other philosophical - that were to ground the distinctiveness of Marx’s theory of revolution as proletarian self-emancipation.

To understand political organisation as ‘expressing’ a set of subterranean relations of course presupposes a philosophical transformation initiated by Marx himself, one more visible in an earlier quotation, this time from The Holy Family (1845). In a broadside against the idealism of Bruno Bauer’s ‘Critical Criticism’, Marx insists on the role of material necessity, on the ‘absolutely imperative need’, as that which drives the workers to assume their ‘world-historic role’: ‘It is not a question of what this or that proletarian, or even the whole proletariat, at the moment regards as its aim. It is a question of what the proletariat is, and what, in accordance with this being, it will historically be compelled to do.’ Visible here is the nucleus of Marx’s methodological transcendence of the distinction between is and ought, fact and value, formulated by his antecedents. Initially reified by Kant’s diremption of the phenomenal and noumenal realms, the former corresponding to the fallen ‘empirical’ world, the latter that of pure virtues untouched by the grubby push and pull of physical causality, it is sutured back together again in Hegel’s conciliatory theodicy of the State, only at the expense of its transformative power (‘what is actual is rational, what is rational is actual’, etc). For Marx, by contrast, it specifies the revolutionary unity of theory and praxis, finding the mechanisms for social transformation in the immanent material motives of a collective agent, its will conditioned by its position within the given relations of (re)production. Pontificating about whether the proletariat should do X or Y, should follow this scheme or that, is thus secondary to the structural pressures that push them in one direction over another, that might in a certain sense compel that choice.

These formulations, which together constitute the enduring differentia specifica of Marxian politics, at the same time produce its characteristic tensions, tensions played out in the successive history of Marxism as a more or less coherent theoretical and political project. The conviction that organisation ought to ‘express’ an existing class struggle, and that the proletariat is in the last instance moved by the tectonic shifts of economic processes, has of course given rise to various economisms, spontaneisms, and determinisms, linked by a certain faith in the movements of history that has as its corollary an excessive reduction of the space of politics. Such a faith has been tested by the various wrong-turns of the labour-movement, its reformism and ‘trade-union consciousness’; not to mention the cataclysms of interwar fascism and the perennial specter of its recrudescence, often more capable of seizing capitalism's contradictions that its supposed gravediggers. Against this, organisation was to be posed not simply as an expression of what exists before or beneath it, but as itself an intervention into the indeterminacy of the proletarian condition, a decision amongst its various tendencies, or an active mediation between the objective and subjective components of class struggle. After all, it was precisely against the not insignificant influence commanded by the utopian and conspiratorial strategies that Marx and Engels’ polemicised, and in this manner they had no issue with telling their proletarian affiliates they were wide of the mark. At the risk of stating the obvious, an attempt to root theory within the proletarian standpoint does not guarantee the adoption of this standpoint by the proletariat as a whole, nor the necessary legitimation of a course of action insofar as it is proletarian. The question thus becomes in what form do communist political organs pursue the effective radicalisation of their compatriots, and by what relation do they stand to the class as a whole. Historically, the hegemonic answer to this question was given by the party, whose various articulations are productive of their own complex set of questions - of the degree of centralisation, of the relation between intellectuals and workers, of internal discipline and external reach - and with them a whole host of problems, most notably that of the parties potential bureaucratisation, its degeneration into an organ of recuperation or domination, of which the troubled history of the communist twentieth century is more than capable of offering plenty examples.

On these issues, Jasper Bernes, in The Future of Revolution (Verso: 2025), makes his position clear. As a study of ‘communist prospects from the Paris Commune to the George Floyd Uprising’, it seeks to track the ‘real movement’ (4) in its historical transformations over a roughly 150 year time period. In doing so Bernes insists on the ‘regrounding of theory in the self-activity of the proletariat’, an unfailing proximity which repudiates ‘any program from above’ and ‘any conception of the party as leader, organizer, or educator’ (11), what he elsewhere refers to as the pastoral or pedagogical conception of organization. The kernel of such self-activity is given by the idea of the workers council: directly-democratic organs oriented toward the immediate seizure of capital by a free association of producers, often crystallising as factory occupations but liable to erupt into insurgent political-economic hybrids, threatening or supplanting state apparatuses. Such an idea is not conjured from on high but posited by the class itself, re-emerging through myriad revolutionary sequences as variations on a theme. By placing himself within this council communist lineage, Bernes counterposes his project to the social democratic or Bolshevik traditions of trade-unionism, Parliamentarianism, or vanguardism; but he also evades a simple spontaneism, a position which Sartre once satirised - and not without a certain accuracy - as seeing the immediate impulses of the workers as ‘good, just, authentic’, as that which ‘moves everyone to pity’ and whose ‘verdict is without appeal, like dogs and children’ [4]. We thus find another layer of Bernes text as an introduction to the ultraleft current known as communisation theory, inaugurated after 1968 as an ‘internal critique of the concept of the council by true believers who found it lacking’ in a ‘new era of class recuperation, economic stagnation, and crisis’ (2), productive of a series of ‘tests’ - necessary but insufficient conditions - that proletarian practice ought to meet. Bernes then extends such a framework to the emergent repertoire of proletarian struggle today, producing a lucid apprehension of its ‘limits’ and possibilities, the future of which the title speaks. Such criticisms should not be mistaken for a theoreticism, however, nor a Leninist ploy to direct the movements of the masses; but simply an attempt to ‘disclose what such struggles would need to learn in order to succeed’ (11), an imputation or extrapolation from their own terms. And it is in this final element that the real significance of Bernes contribution, as well as its tensions, resides.

The Good Old Days, and the Bad New Ones

Its crux might be encapsulated by Brecht’s famous exhortation not to ‘start with the good old days, but the bad new ones.’ Capital, absent a growth engine comparable to the Fordist manufacturing industry, has found its room for maneuver truncated. No longer capable of mollifying social struggle through the provision of concessions - the halcyon days of industrial organising, Clover reminds us, proceeded apace with the expansion of accumulation, dependent upon the ill-discipline of taut labour markets and the existence of a social surplus large enough to portion out [6] - the reproduction of bourgeois social relations proceeds increasingly through the intensification of state repression. Unable to valorise effectively through production due to systemic overcapacity, capital has trundled toward the sphere of circulation, competing for dwindling profits and market share ‘by decreasing its costs and increasing turnover time for an ever greater volume of commodities' [7]. As capital chases returns in the FIRE sector, this manufacturing downturn articulates itself through the wider economy as a slowdown in investment and a reduced demand for labour [8]. Hence a notable expansion in what Marx termed the ‘reserve army of the unemployed’, those oscillating in and out of labour markets in conjunction with the business cycle, condemned to long-term underemployment below the cost of their reproduction and participation in unregulated ‘informal economies’, particularly amidst the trash-pickers and street-vendors of the Global South. And as the surplus-population expands, so too does the carceral state and its foot-soldiers. While Bernes devotes little attention toward elaborating these shifts, appearing for the most part as scattered scene-settings to differentiate the relevant historical sequences - ‘as the rate of growth of capitalism has slowed’ (7); ‘the locus of action was no longer in the workplace alone’ (158), etc - Clover is more explicit with his influences, mapping Giovanni Arrighi’s account of systemic cycles of accumulation onto Robert Brenner’s analysis of the ‘Long Downturn’ from 1973 onward.

These kinds of intricate periodisations are part and parcel of the communisation theory approach, heuristics that insist on the stringent historicisation of antagonisms through their specific structural determinants; the result is a Marxism largely shorn of subjectivist moralism or objectivist cynicism, and all the better for it [10]. For Bernes and Clover, such a method yields a thesis as to the centrality of what the latter called ‘circulation struggles’ as the immediate modality of class-struggle today: un- or under-employed proletarians, unable to affirm themselves as such through organising at the point of production, instead disrupting capital in its spaces of circulation in the form of riots, blockades, occupations, etc, and always dogged by the strong-arm of the state. Such tactics constitute means to set the price of their reproduction down to zero, be they through the formation of autonomous zones or looting, and thus exist in a certain continuity with the moral economies of pre- or incipiently capitalist riots. The principal gift of Clover’s work was to render the riot, as this paradigmatic tactic of contestation, intelligible as a rational form of struggle corresponding to a definite structural condition; to see it not as the spasmodic opposite of the (orderly, juridical) strike, nor in need of others to speak on its behalf, but as capable of saying its own name and of specifying its own demands. Against those who might resist this departure from the conventional protagonists of the workers movement, Clover concludes that ‘normative arguments about what people who struggle should do miss the most basic truth. People will struggle where they are' [11]. Bernes, maintaining this fidelity, concurs: ‘one must work with the terms which the proletariat has already chosen’ (169).

Corollarous to this, of course, is a thesis as to the terms that the proletariat has not chosen, and here we find Bernes and Clover largely dispensing with the paradigmatic forms of proletarian organisation in the twentieth century, trade union and mass party. In part this is a casualty of the structural trends we have elucidated above, the fragmented legal and political geographies from which such forms derived much of their power, in which the spatial concentrations of industrial production had given way to the dispersal of service work and underemployment, and the consecration into law of the notorious defeats of organised labour that christened the neoliberal counter-revolution. But it is also clear, if only by the selection of his interlocutors, that Bernes is rather sceptical toward the leadership claims of such institutions, whatever their conjunctural health. Claude Lefort, for instance, who occupies an important position in Bernes discussion of the postwar council communist tradition, was withering in regard to their role in the stabilisation of capitalist social relations - mere ‘forms for the enrollment of labour power within that system’ [12] - and deeply suspicious of the party’s assertion of superior knowledge, to be foisted from without onto the proletariat as passive element.

Apart from these implicit resonances, Bernes indicates his opposition by the narrativisation of sequences in which such organs meddled to terrible effects, with the lengthy discussion of the role of the SPD in neutralising the radical tendencies of the German Revolution being exemplary. Nevertheless, the interweaving of these structural-historicising claims with an evident political antipathy at least raises the question that these forms may not necessarily be as obsolete as our authors might like them to be, and creative thinking about how they may be adapted to a new conjuncture is largely ignored [13]. We do not need to be nostalgic for the Keynesian class compromise to recognise that such institutional modes oriented themselves, at least on paper, to certain indispensable functions - the massification, coordination, and intensification of proletarian political capacity - for which we do not have an easy alternative.

In any case, one of the principal questions which looms over such discourse, at least from the external point of view, is that of the relation between diagnosis and prescription. We are justified in asking whether correspondence to a structural trend unto itself indicates political effectivity: of whether, say, riots comportment to the fragmentation of the labour movement and the doldrums of accumulation is tantamount to being their negation, as Clover claims - or, better yet, their determinate negation, as that which is able to break the symbolic confines of what it opposes - rather than simply their expression or mirror-image. Plenty of half-baked political strategies might in a certain sense accord with the conjuncture without being capable of challenging it. The programme of left-populism, which constituted the parliamentary opposite of Clover’s circulation-struggles, is a case in point: an expression of the post-institutional state of the workers movement [14], the Pasokification of legacy social democratic parties, and their replacement by lithe ‘digital parties’ and ‘hyperleaders’ as the organisational couplet to the age of platform capital [15]. This interpretive problem is situated right at the core of Marxism as research method and political project, and insofar as its claim to a certain scientific orientation holds up, it of course pivots on the capacity of its composite conceptual elements - mode, forces, relations of production; regimes or cycles of accumulation; value, crisis, reproduction: take your pick! - to explain structural relations and tendencies in such a way that praxis may be oriented for maximal effect. But unless one wants to simply read off political strategy immediately from such tendencies, then a certain autonomy of interpretation and prescription - in other words, a certain autonomy of the political - is involved; the capacity to pose structural determinations as a terrain over which one must maneuver one way or another. The challenge is thus to avoid the scylla of spontaneism - in which proximity to the real movement deteriorates into what Lukacs pilloried as ‘tailism’, always trailing behind what happens to be thrown up by the given relations of class forces [16] - and the charybdis of voluntarism - in which the complex articulation between is and ought characteristic of Marxist method gives way to the petulance of the subjunctive, to be imposed on the class by an external force.

Bernes, in his aforementioned encomium for Clover, argues that many misread the text as a ‘programmatic endorsement of riot, rather than a passage to its limit.’ This may be the case, but such a misinterpretation certainly indexes something important. As Alberto Toscano writes,

we can’t exercise punishing sobriety regarding the chances of traditional proletarian conflicts at the point of production while infusing what are still remarkably weak, disconnected, and often politically ambiguous riots – whose main use thus far has been as occasions for strategies of state and capital – with such strong messianic power, especially when the conditions of their scalability and articulation are entirely enigmatic. [17]

One ought to read The Future of Revolution as an extended answer to this challenge, an attempt to precisely elucidate the ‘limits’ left somewhat ambiguous in Clover’s work, and the conditions of ‘scalability and articulation’ their transcendence presupposes.

To Set Fire to Fire

In order to extend the riot, then, Bernes first retrieves the workers council from the past as key to the future. His narrative is structured by the elaboration of certain core principles that must be met, not just for an effective implementation of the council form, but as necessary conditions of revolution itself. The story begins in 1871 with the Paris Commune, what Marx famously deemed the ‘political form at last discovered to work out the economic emancipation of labour’ [18]. Such a designation was premised on three core features: the demobilisation of the standing army, the liquidation of the parasitical bureaucratic class, and the replacement of bourgeois (mis)representation with a system of mandated and recallable delegation, thus instituting a kind of ‘supervision from below’. Nevertheless, the Commune was hobbled by all sorts of failures, not least of which was its inability to overcome the distinction between the political and the economic: its radical democratic organisational structure was marked by the absence of any coordinated production for social need, and the spread of delegation was, in truth, unduly limited. On this basis, Karl Korsch later lamented the ‘dangers of such formalism’, insisting on strict proletarian content - its ‘revolutionary, working-class character’ - over a form that could just as well consolidate bourgeois communitarianism. Bernes demurs, insisting on delegation as a ‘necessary though by no means sufficient condition’ (30-32), one whose importance is ratified by its extension to the workers councils of the 1905 Russian general strike. The commune and the council thus exist on a continuum of autonomous organisation, selected by the emergent self-activity of the masses. The latter renders the commune-form within the point of production and thus, so the idea goes, suggests a closer proximity to its communist content.

Barricade Voltaire Lenoir, Paris Commune, 1871

Bernes extracts from this opening discussion four criteria that the council ought to meet, testing them through the experience of subsequent struggles:

- It must institute mandated, recallable delegation, in which sovereignty resides with the base assembly and is lent upward through coordinating committees. Despite this aspiration, the actualities of many councils fell short, particularly the soviets of 1917, in which a process of bureaucratisation tended to consolidate power in the hands of party apparatchiks.

- It must be a political-economic ‘amphibian’, capable of transcending the formal distinction between spheres instituted by capitalist social relations and the inhibiting division of labour between unions and parties that results. The fracturing of councils into one mode or another was pivotal in the failure of the German Revolution, recuperated by the SPD as addendums to a constitutionalism that sought to stabilise social antagonisms; and their inability to pose an effective revolutionary challenge in Italy’s biennio rosso, or ‘two red years’, wedded to a syndicalist orientation which refused to pose the political problems of composition, expansion, direct expropriation, and so on.

- It must be intensively and extensively coordinated, ‘filling workplace with plenary mass’ and ‘expanding from workplace to workplace’ (42). Once again, the consolidation of factory councils across Milan and Turin in 1919-20 serves as foil here: ‘highly localised’ and ‘negotiated confrontations with the state and employers rather than insurrectionary explosion’ (64).

- Finally, it must represent a fusion of form and content: not simply imperative mandate, nor proletarian power, but their interlocking in a single mode of revolutionary self-organisation.

In short, the assertion of workers' self-management as lynchpin of the council makes increasingly less sense in an age of labour’s decomposition. Bernes attributes an incipient recognition of this shift to Debord and the 1962 Situationist text ‘The Bad Days will End’, anticipating the 'structuring logic of revolt in the coming era, featuring attacks not only against the machinery of production, but also that of consumption, transportation, communication, and information’ (138). Indeed, it is for this reason that Clover ends Riot. Strike. Riot. portending not the return of the council but the commune, offering a ‘broader social scope’ that ‘comprised […] both production and consumption’ [19]. There is thus a sense in which - as Bernes’ narrative unfurls toward the contemporary space of circulation-struggles - it depicts the crucial becoming-commune of the council, expanding the category of proletarian to include not simply the waged but all those ‘without reserves’, liable to directly expropriate the productive forms around them without relying on the firm-bounded ‘self’ of classical self-management (144). The geometry of revolution is thus no longer a circle, radiating out from production, but an ‘ellipse’, with ‘one focus eccentric to the workplace and another within it’ (158), its compositional forces striving to bridge the gap.

Moreover, a focus on the point of production tends to occlude the manner in which capital dominates not simply through internal relations of command in the workplace, but also through the compulsions of value in the marketplace. Units of self-management thus risk transformation into units of self-exploitation by the lateral coercion of competition, as evinced by the withering critique of the 1973 Lip factory occupation advanced by the journal Negations [20]; or become dependent upon the state for their survival by means of credit or nationalisation (157). An inability to theorise this fact proper was linked to the hegemony of what communisation theorists call the ‘programmatism’ of the conventional workers movement, in which the affirmation of workers qua workers was coextensive with the re-appropriation of the machinery of the state and capital in the transitional stage to communism. In a by now familiar historicising move, however, such a conception was dependent on ‘the rising power of industrial labor’, a condition which no longer pertains. In its place is posited ‘communist measures’ as procedures of immediate socialisation and provision outside of the wage- and money-relation, rendering the production of communism not as an end to be deferred but as an expanding wedge to suspend the reproduction of capital. Following the work of Giles Dauvé - êminence grise of communisation theory - emancipation must thus be considered not a ‘form of management (or distribution)’ but the absolute ‘destruction of the law of value’: the abolition of state and capital and its substitution by ‘provisioning for common use according to a common plan without legal regulation or exchange’ (128). An emendation of this substitution constitutes the task of chapter two, a somewhat recondite intervention into value-form debates as a means to furnish what Bernes calls the ‘test of value’ and the ‘test of communism’, essentially the pars destruens and pars construens of an alternative mode of production.

This all comes to a head in Bernes’ analysis of the George Floyd Uprisings of 2020, the capstone of the text in which the relation between diagnosis and prescription is brought into sharpest relief. The GFU is emblematic of the contemporary cycle of struggles, a surplus-rebellion in which differential subjection to state power intertwines with racialised exclusion from the labour-market. Such ‘movements emerge eccentric to production, and their passage to insurrection this way tends, leading to a politicisation of struggles that are curiously antipolitical in character and therefore unable to follow through in demands’ (159). Here we find a clear apprehension of the limits of such movements, a refusal to fetishise their externality to production and the imprecise nature of their opposition, oscillating between the erratic maximalism of the riot and the reformism of their electoral co-optation, anxious to disown the former’s violence as springboard for state legitimacy. The analysis that follows is structured by the metaphor of fire, illuminating both the crisis of governability imposed by the riots onto the repressive apparatus, and the difficulty faced by the participants in corralling those resistive energies into a coherent revolutionary project. At their intersection is the burning of the Third Police Precinct in Minneapolis, a ‘replicable action’ that prompted the possibility of establishing autonomous zones that multiply and expand. ‘Fire demobilises the police’, shifting them toward ‘passive protection of firefighters, traffic control, and the defence of key sites.’ But fire is also ‘uncontrollable’, ‘directed by physical variables not knowable in advance’, and tends to ‘erode its own conditions for reproduction’, exhausting itself without supplies of ‘air and fuel’ (166-167). Bernes repeatedly invokes the necessity of ‘coordination and extension’, but finds no organ capable of executing this function amidst the smoke. At this point he takes recourse to the speculative mode:

What if […] in these early days, a vast abolition assembly were held, the result of which was the formation of an abolition committee and the permanent occupation of a given space? What if this spread to other cities? What if these committees could wax and wane as the movement went through its phases, extending the energies of some initial moment into subsequent insurrectionary heightening? [...] they would need to serve as critical reflector and amplifier for the content of struggle itself, for the distribution of viable tactics and forms that might sharpen the movements' means and clarify its end, extending the energies of the riots into new social categories and spaces. They would need to catalyze action among non-militants and non-activists, in workplaces, schools, prisons. They would need to establish correspondences, through print and other media, and in this way allow for self-reflexivity (170).

Here we find the re-appearance of the council, with all its necessary conditions implied, as operator of the riots development. But Bernes immediately qualifies his pre-emption: the ‘abolition committee’ is nothing but a ‘heuristic fiction’; such forms emerge only ‘by necessity and not by choice’ (170). In other words, it is not a matter of what the proletariat takes as its aim, but what the proletariat is, and what, consequent on this being, it will be be compelled to do.

Necessity and Choice

This assertion as to the primacy of necessity over choice exposes a tension in Bernes’ account. On the one hand, he is emphatically opposed to any ‘educative’ relation to the working-class, any attempt to intervene prescriptively. Militants 'can participate in struggles, learn from them, and report on them’ but they cannot think they ‘might shape or organise them’ (12). As a result, Bernes has a tendency to invoke the agency of history as a solution to the vexations of struggle, as when he writes that the division of labour between intellectuals and class, the ‘gap’ between them, is ‘not a hole in organisation [...] but a hole in history’, or that ‘only history itself can provide a positive form and a positive content’ (149, 160). In a gesture that no doubt has the intention of deferring such organisational questions to the class as a whole, it has the effect of rendering its political will as a kind of natural force, shunted into play by the causal chain of crisis and instability. On the other hand, Bernes simultaneously assumes responsibility for setting the class crucial ‘tests’ that it ought to pass; and note here the telling persistence of the pedagogical register he attempts to distance himself from. His thematisation of the ‘limits’ of spontaneous practice is productive of a series of conditions that it should meet, and however much one wants to say that such conditions are immanent to this practice, they nevertheless present themselves as independent theoretical criterions. Insofar as Bernes concedes the possibility that practice may or may not satisfy these criterions, he therefore reinjects the fact of choice, the problem of will and decision, into that matrix of history and necessity. Once this room for maneuver is admitted, the question is no longer whether one is committed to shaping the course of events or remaining largely passive, but whether or not one's organisational precepts are adequate to meet the posited ends.

If we cannot trust history to deliver the ‘abolition committee’ by itself - or, at the very least, in the form Bernes’ tests require - then what is there to prepare the ground? His answer consists in a somewhat equivocal discussion of the party as function rather than form, and a programmatic rendering of workers inquiry as a means to establish ‘liaisons’ between fractions of the class and ‘inventory’ local means of production in preparation for their expropriation. The first intends to free the party from the reifications of specific organisational modes - classically, the ‘centralising, decision-making vanguard of the revolution’ - and renders it simply as that function which initiates ‘the overcoming of capitalism and the production of communism’ (148). This rather vague gesture is supplemented with the notion of the party as catalyst from Jan Appel, leader of the ultraleft splinter group KAPD during the German Revolution, for whom the ‘the party […] is neither a quantitative form, swelling with masses, nor a qualitative one, deepening with discipline, but [...] a vanishing mediator that gives way to direct workers power’ (53). Bernes ascribes all sorts of wonderful things to this mode: it propagates revolutionary examples (e.g, councils, direct expropriations, etc); it serves as a ‘transistor’ that ‘amplifies’ what is critical in ‘proletarian practice’; and leads only insofar as it provides a ‘framework, a nucleus, derived from the proletariats own actions’ (163, 53). As a concrete organisational form, the KAPD operated as ‘loosely coordinated, autonomous armed groups’, intent on ‘extending and defending moments of insurrection while reproducing themselves through expropriations.’ In the present, Bernes asserts that ‘what matters organisationally are sites that broadcast and amplify the reproduction of struggle’ (164), thus tending to collapse this notion of the party into the aforementioned notion of a hybridised workers inquiry.

The thrust of workers inquiry, as formalised by the midcentury council communist tradition, is to produce an alternative model of the subjective dimension of class composition, one that contests the paternalism of the Leninist importation of consciousness-from-without. Bernes tracks well its emergence in C.L.R. James’ Johnson-Forest Tendency in the United States, its adoption by dissident French Trotskyists in the work of Socialisme ou Barbarie, and later by the Quaderni Rossi group centred around Mario Tronti and Raniero Panzieri in Italy. The intention of such a technique is to render the militant nothing more than a relay in the proletariat's own self-clarification. Organisation becomes a matter of provoking the conscious thematisation of relations of exploitation by the workers themselves, assisted by elaborate sociological questionnaires or solicitations of worker writing, in order to extract from these the ‘trace of the collective comportment within individual, fragmentary accounts’ [22]. Bernes notes the risks of such a model, sometimes tending to overinvest the immediate capacities of the workers with a revolutionary potential that is unwarranted, other times tending toward a quietism borne of the ‘anxiety of influence.’ This latter fate is what befell the successor group of Socialisme ou Barbarie, Informations et Correspondance Ouvrieres (ICO), in collision with May 68’, when, amidst the notable workers-student occupations of the Sorbonne’s Censier campus, they decided to lock themselves away in a separate room lest they ‘spoil proletarian self-activity’ (147). Nevertheless, in ICO Bernes finds a clear model of what militants should do in non-revolutionary times: ‘establish resonances, networks, and correspondences among the most revolutionary members of the class; pay attention, in order to discover the sources of class conflict, follow the new contours of class struggle, and anticipate the shape of coming self activity’ (136). When the contradictions come to ahead, such groups are to dissolve themselves into the proletarian currents, their methods taken up by ‘inquiry committees’ charged with producing ‘knowledge [...] of existing resources’ (171) as a prelude to their seizure. There is something quite thrilling to this picture; the ruptural moment deepened and complexified by the construction of a ‘blueprint’ for its strategic orientation. The George Floyd Uprising, Bernes reflects, ‘lacked clear goals or targets’, unaware of ‘where the sites of power lay’ (172) - but what if it didn’t?

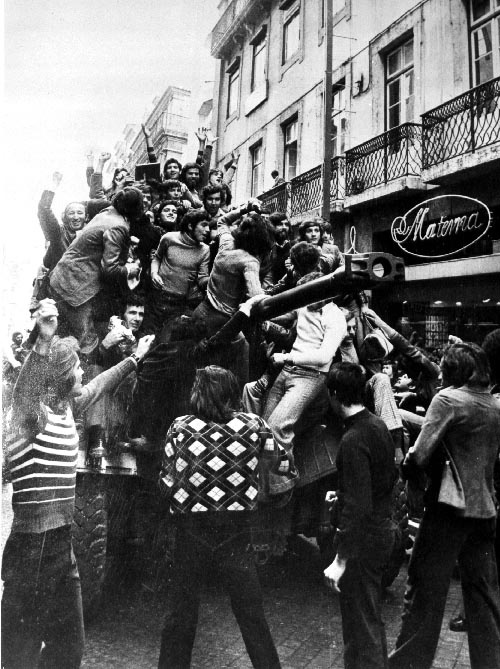

Portuguese protesters climb an armored car during the Carnation Revolution, 1974 (Credit: Centro de Documentação 25 de Abril, via Wikimedia Commons)

Such is the wager of Bernes’ insurrectionism. But precisely as such, it gives rise to a series of concerns. First, one gets the sense that he may be overinvesting in the effect of conjunctural circumstances to shift the masses into a revolutionary mode. Throughout his work, the speculative extrapolations of a communising sequence often begin with spectacular moments of crisis [23]; and whilst it would be naive, if not anti-materialist, to exclude these moments from a Marxist politics (we might say they are a necessary but insufficient condition of revolution) it is equally misplaced to hitch ourselves to their timeframes, to telescope the political into the weeks and months where it appears in its most heightened state. Bernes does indeed contend that we must both ‘organise now’ and ‘wait for an opportune moment’ (163), but the weight of his theory tilts firmly toward the latter [24]. Recall that all he permits us to do in non-revolutionary moments is ‘speculate’ and ‘catalog the internal limits of revolutionary practice’ (15). Here we find what Rancière once criticised as times function as a ‘prohibition-operator’ in historical materialism, classically invoked to question the ripeness of objective circumstances, albeit now in a decidedly anti-Leninist mode: one must simply wait and see what the proletariat throws up, and then, and only then, might one start to agitate proper. But the effect of this is to contract the temporality of struggle into the white-heat of an insurrectionary sequence, one whose fractiousness tends to increase the difficulty of the patient explorative, deliberative, and persuasive work organisation requires. As a result Bernes tends to rely upon a quasi-naturalist notion of ‘mimetic’ contagion as answer to the obstacles of coordination and extension. Whatever merit this has as a descriptor of certain kinds of spontaneous tactical diffusion, it cannot substitute for attempts to pose the composition of a potent social force as a strategic problem, one involving complex negotiations across class fractions, a lengthy building up of capacity across spatial and infrastructural boundaries, the development of a shared programme, and so on. Whilst these efforts are never exhaustive, they surely establish indispensable organisational resources in relation to which more spontaneous logics play out. Without this, what is to say that such a mimetic contagion won't work in the opposite direction, a kind of repulsion or splintering of struggle given the mediations of the conflict through bourgeois apparatuses of various kinds - or, worse, spurring allegiance to fascistic counter-mobilisations in the name of order? Bernes, to give him his due, does task the abolition committees with ‘the cultivation of organisational capacity outside the milieus typical of the left’, extending into ‘workplaces and neighbourhoods’ (171). But if we only begin such projects in earnest at the point of ignition, we run the risk of these efforts being too little, too late [25].

Second, matters are made worse by the strangely technicist model of inquiry he sets forth, dressed up as a kind of neutral diagnostic in attempts to ‘inventory’, ‘relay’, etc. Thus we can ask, ‘what do people do for work where you live? What is produced, using what inputs?’ (171). But one only gets the answers people are prepared to give, and in such moments we ought not to take for granted a level of receptivity that might not exist. While it is clear why Bernes takes this position, in keeping with his resistance to the aforementioned pedagogical mode, a more interventionist or programmatic conception of organising is perhaps implied by his own conditions. Recall the importance of the fusion of form and content in the council, which is re-emphasised with the case of the Portuguese Revolution. Hamstrung by the principle of self-management, such councils never posed the demand for the abolition of ‘markets and money’; the radicality of their calls for autonomy were couched in a petition for ‘improved conditions’, and the result was that they were ‘forced to work at cross-purposes’, mediated through the state and competitive relations, therefore undermining the ‘construction of conciliar power’ (157). But if a recurrent problem of emergent council forms is a weakness of revolutionary content, this reintroduces the centrality of theoretical acuity, programmatic direction, and organisational cohesion; and whatever its other weaknesses, it is the party that, as an attempt to organise and propagandise an explicit proletarian politics, claims a comparative advantage in these domains. It was precisely this problem that, in part, motivated Cornelius Castoriadis - co-founder of Socialisme ou Barbarie along with Lefort, whose tense collaboration constituted the two poles around which the group oscillated - to defend the programmatic form of the party from his erstwhile comrade, noting that ‘revolutionary politics [...] necessarily implies making a choice among the things the working class produces, asks for, and accepts’. It should also be said that, for Marx and Engels, there was no contradiction between the insistence on proletarian self-emancipation, with communist activists and theoreticians rendered the ‘mouthpiece for what is happening’ [27], and their pugnacious attempts to ‘win over the European [...] proletariat to our conviction’ [28]. And despite the metaphorical force of the notion of party as catalyst, there is something quite lacklustre about Bernes’ formulation, which fluctuates between establishing networks and correspondences between militant fractions of the class - surely a central function of any political organ, especially given the dispersal of our conjuncture, but one that, in such a presentation, conceals the task of expanding and cohering the circle of affiliates - and simply highlighting ‘forms, like the councils’ (149), that might be put to use.

Finally, if we concede both a more complex strategic temporality, and the importance of programmatic cohesion, we ought to reconsider the necessity of their more muscular institutional implementation, a problem Bernes largely sidelines in his attempts to render the party as a function rather than as a specific form. As a supplement, we ought to look to his essay for Endnotes, ‘Revolutionary Motives’, which culminates in a distinction between ‘adventurist’ and ‘vanguardist’ groups: while the former utilises ‘communist measures’ (essentially, the free distribution of expropriated goods in autonomous zones) as the means to ‘provide the material basis upon which they will freely choose to go in the direction of communism’, the latter deploys ‘moral and pedagogical re-education campaigns, organisational hierarchy, monopoly over resources, direct violence, incentive structures, and other forms of instruction and compulsion’ [29]. In formulating such a distinction, Bernes relies on Sartre’s account of the degeneration of the ‘fused’ into the ‘institutional’ group in the first volume of his Critique of Dialectical Reason, in which the stabilisation and formalisation of role-positions out of the spontaneous unity of a riot or occupation (Sartre departs from the storming of the Bastille) portends the re-inscription of violence as a mechanism of hierarchical discipline and institutional reproduction. But both Bernes and Sartre tend to conflate organisational stability with its hierarchisation, excluding the possibility that the exercise of institutional roles can be selected and delimited through direct democratic processes, i.e., through mandated delegation and supervision from below. That the council-form can avail itself of such mechanisms but the party can not is never made clear by Bernes. Indeed, Castoriadis made exactly this point in his formulation of the principles of an alternate revolutionary party, contrasting favourably to Lefort's cliquish invocations of worker newspapers. (It should be said that all the organs Bernes points to as carrying forth the spirit of inquiry are magazines, run by small teams of editors; and one cannot help but counterpose these to the remarkable reach of the mass membership social democratic parties of decades past, establishing counter-institutions which served as sites of assembly, solidarity, and exchange.)

Moreover, the idea that one could simply circumvent the problem of stabilising and formalising group-praxis - that is, the problem of its institutionalisation - through the model of ‘exemplification’ is belied not only by the mediation of social relations required by the effective scaling and integrating of communist measures themselves, but also by Bernes own careful apprehension of the internal disorder of the George Floyd Uprising. ‘As looting became more dispersed and technically complex’ it also became less communist, appropriated by criminal gangs. Autonomous zones were ‘effectively lawless’, to which opportunists flocked like moths to a flame. What was required was the ‘establishment of an ethical and organisational consistency’ (168), and it does not seem too much of a projection to read this as a euphemism for discipline. How exactly such discipline is to be democratically formulated and enforced is a question I cannot answer; that it ought to be is a requirement suggested by the complexity of the situation itself.

Anxiety of Influence

Despite these concerns, I see no real contradiction between an assertion of the necessity of a kind of council-party, in the model favoured by Castoriadis, and many of the organisational techniques Bernes favours: a movement of communists, cohered democratically around a determinate programme, militating to build up capacity across waged and unwaged class fractions (work that includes investigation and correspondence as much as persuasion and agitation) before the revolution, and intervention as propagating factions of the council-forms that arise during it [30]. Crucially, such a conception does not preclude a bilateral relation of influence here and, insofar as it takes seriously the manner in which sovereignty resides in base assemblies, in fact presupposes it; that the party learns from the masses in its dialogue with them is thus central to a properly dialectical model of ‘leadership’, ‘pedagogy’, or, indeed, theory. In fact, this seems to me more able to meet Appel’s designation of the party as catalyst than the somewhat noncommittal procedures of inquiry Bernes stakes his conception of preparatory work on, and it is a shame that this notion of catalyst is not more developed. Indeed, outside of a smattering of Trotskyist screeds and historical abridgements, the Marxist theory of the party as such - a theory which would include all those who opposed it as equal interlocutors - remains somewhat untold. Such a narrative ought to follow Bernes in specifying the party as function - as that which attends to the problems of programme, composition, and extension, problems which are acknowledged but which lack a convincing answer in his account - without at the same time denying the importance of its institutional objectification, the possible variety and plasticity of which cries out for thematisation. The Future of Revolution nevertheless remains a bracing and indispensable attempt to work through the problems of revolutionary strategy, unburdened by the truisms of centuries past.

Bernes might well fear that the above criticisms risk a return to a kind of ‘pedagogical’ relation to the masses, but part of what I wish to argue is that such a fear is a red herring: all Marxist politics, insofar as it is a politics (and not a mechanistic philosophy of history), is a matter of different attempts to influence or guide the course of proletarian contestation, including that of Bernes, with the differences lying in the how and why of such influence. This is occluded by a certain ultraleft tendency to portray programmatic interventions tout court as necessarily suspect or instrumentalising, thus having the effect of claiming some greater affinity or solidarity with the authentic working-class against petty-bourgeois intellectuals and interlopers. Bernes does not reproduce this tendency: he has little time for the aforementioned isolationism of ICO, offering a coherent model of organisation as workers inquiry and exemplary action (although we should note, in passing, that this model of exemplification is not unto itself anti-Leninist; Lukacs, for instance, saw it as key to the ‘imputation’ of revolutionary class consciousness), concurring with Dauve that the ‘wish to create the party and the fear of creating it are equally illusory.’ But this ambivalence, combined with the elision of the party as concrete organisational form, and the restrictions that follow from his model of inquiry, tend to rather truncate the space of the political. The result is that Bernes, despite his trenchant critique of ICO’s anxiety of influence, ultimately seems limited by some of his own.

1. Engels, Anti-Duhring (1877), cited in Lowy, The Theory of Revolution in the Young Marx (Haymarket: 2005), p.15

2. Marx and Engels, ‘The Communist Manifesto’ in Karl Marx: Selected Writings (OUP: 2000), p.251-252

3. Cited in Draper, ‘The Principle of Emancipation in Marx and Engels’ (1971). Accessed: https://www.marxists.org/archive/draper/1971/xx/emancipation.html

4. Sartre, The Communists and Peace, with A Reply to Claude Lefort (Georges Brazilier: 1988) 101

5. Bernes, ‘For a Summer Against Ice’ (2025). Accessed: https://www.versobooks.com/en-gb/blogs/news/for-a-summer-against-ice-in-memory-of-joshua-clover?srsltid=AfmBOoqNynK_q29CF5VJ_cediLTru6OoCIFQK7vBVNRg2N7K725B1-P0

6. Clover, Riot. Strike. Riot (Verso: 2016), p.106-107

7. Ibid., 141

8. See Benanav, Automation and the Future of Work (Verso: 2020)

9. See, for instance, Sic Journal, ‘On the Periodisation of the Capitalist Class Relation’ (2011). Accessed: https://www.sicjournal.org/on-the-periodisation-of-the-capitalist-class-relation/index.html)

10. Clover, Riot. Strike. Riot. (Verso: 2016), p,144

11. Lefort, ‘Organisation and Party’ in Socialisme ou Barbarie: An Anthology (ERIS: 2018), p.317

12. An attempt to mark out an alternative unionism, in response to Bernes, is provided by Nate Holdren: https://buttondown.com/nateholdren/archive/the-future-of-revolution-book-review-and-response/

13. See Jager and Borriello, ‘Making Sense of Populism’, Catalyst 3:4 (2020)

14. See Gerbaudo, The Digital Party: Political Organisation and Online Democracy (Pluto: 2018)

15. Lukacs, A Defence of History and Class Consciousness: Tailism and the Dialectic (Verso: 2002)

16. Toscano, ‘Limits to Periodization’, Viewpoint Magazine (2016)

17. Marx, ‘Civil War in France’ (1871)

18. Clover, Riot. Strike. Riot, (Verso: 2016) p.189

19. See Brown, ‘Red Years: Althusser’s Lesson, Ranciere’s Error, and the Real Movement of History’, Radical Philosophy 170 (Nov/Dec 2011)

20. Clover, Riot. Strike. Riot., (Verso: 2016), p.149

21. Hastings-King, Looking for the Proletariat (Brill: 2014), 121

22. Bernes, ‘Revolutionary Motives’ in Endnotes: The Passions and the Interests (2019), p.243-244

23. Julian Francis Park advances a similar critique in ‘The Workers’ Council Redeemed?’, The Brooklyn Rail (May 2025). Accessed: https://brooklynrail.org/2025/05/field-notes/the-workers-council-redeemed-on-jasper-bernes-the-future-of-revolution/

24. Bernes does, in passing, register the importance of building up ‘base unions’ and ‘workplace committees’ (173) as a corrective to the externality of contemporary struggles from production, and one can assume such endeavors are to operate on longer timeframes. But this is the exception that proves the rule.

25. Castoriadis, ‘Proletariat and Organisation’ (1959), in Socialisme ou Barbarie: An Anthology (ERIS: 2018) p.333

26. Cited in Lowy, The Theory of Revolution in the Young Marx (Haymarket: 2005), p.139

27. Ibid., p.119

28. Bernes, ‘Revolutionary Motives’ in Endnotes: The Passions and the Interests (2019), p.246